Low interest rates are the final straw for many company pensions

By Michael A.

Fletcher, May 24, 2013 - The Washington Post

In INDIANAPOLIS — It was no small matter for the ILM Groupfs executives when

they froze the pension plan that has provided retirement security for the firmfs

employees since 1947.

The financial pressure of maintaining the plan had been mounting on the small

insurer for years. But until March, ILM had not given in, even as tens of

thousands of other employers did. It held on when the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist

attacks rocked the economy, flat-lining the stocks that fund the pension

payments. It also kept the plan intact when the Great Recession shrank its

holdings by 29 percent.

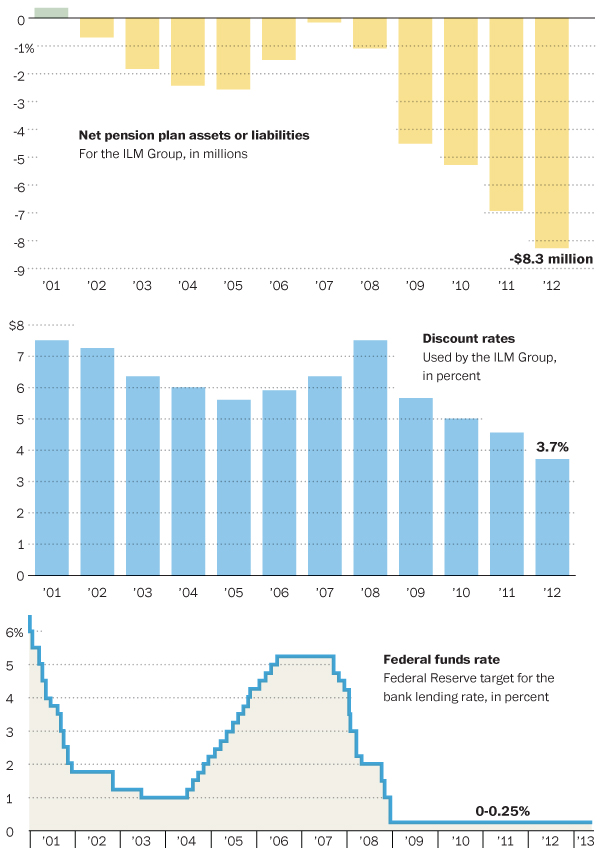

What finally did the plan in? Rock-bottom interest rates. The very rates, in

fact, that helped fuel a stock-market rally and brought ILM double-digit returns

on its pension-fund investments in each of the past three years. But because of

an accounting twist, the near-zero rates also caused ILMfs projected pension

obligations — like those of every other private company that still provides a

traditional pension — to spike, overwhelming the stock-market gains.

To calculate pension obligations, companies have to factor in the future

value of money. Accounting rules peg that value to interest rates on corporate

bonds. If bonds have a high interest rate, you can assume a high value for

future dollars. But if rates are low, the dollar is low, and it takes more of

them to meet future obligations.

So when interest rates go down, the projected obligations go up, requiring

the firms to set aside more cash today to pay retirees in the future. For ILM,

that meant funneling more than $2 million — roughly 22 percent of its payroll —

into its pension fund over the past two years. The expense was too high to keep

it up, the company decided.

Its board members had a long, agonizing debate about whether they should hold

out a little longer, hoping for interest rates to rise.

gThis was a huge decision,h ILM President John Wolf said. gThis was a

fundamental promise to our employees, and we did not want to renege on that. You

want your employees to have a good life after they work decades. But with the

way things were, we had no choice.h

The company sent an e-mail to its 64 employees breaking the bad news.

gYou know these people, and you know a decision like this affects their

lives,h said Susan Knotts, ILMfs vice president for human resources. gItfs a

tough call that affects us, too.h

The experience of ILM speaks to a new challenge confronting the old models of

retirement security in a turbulent and fast-changing economy. For generations,

the unprecedented gains in living standards enjoyed by the nationfs retirees

were boosted by employers who offered longtime workers a fixed benefit for life

once they retired.

But that benefit is increasingly rare. Many private firms stopped offering

traditional pensions and switched to 401(k)-type accounts, in large part because

government rules aimed at ensuring the financial viability of the traditional

plans made it more expensive for employers to provide them.

The financial risk posed by pension plans only increased when a long era of

ever-steady stock-market gains ended in 2000, giving way to more volatile returns. Now,

meager interest rates are squeezing the fast-dwindling number of traditional

pensions still offered by private employers, even as policymakers are searching

for ways to bolster retirement savings.

Assets held by pension plans of the firms that make up the Standard &

Poorfs 500-stock index increased by $113.4 billion in 2012, according to a

report by Wilshire Associates, a consulting firm. But largely because of low

rates, company liabilities increased even more: by $173.6 billion. That left the

median corporationfs pension plan 76.9 percent funded, with just over $3 of

assets for every $4 of liabilities.

Low interest rates hurt firms that provide pensions in two ways: They are

required to set aside more money to pay for future pensions even as the

liabilities appearing on their balance sheets grow larger.

gLow interest rates are certainly a significant issue for employers,h said

Judy A. Miller, director of retirement policy for the American Society of

Pension Professionals and Actuaries. gThe lower the interest rates, the higher

the value of the benefits you have to provide and the higher the required

contributions.h

The number of employers offering pensions that pay retirees a fixed benefit

for life has been in steady decline for more than three decades. The Pension

Benefit Guarantee Corp., the federal agency that insures private-sector pension

plans, reports that the number of plans it insures for individual employers

plummeted from 112,208 in 1985 to 25,600 in 2011.

Towers Watson, a benefits consultancy, has said that over the past decade

most Fortune 100 firms have shifted from offering traditional defined-benefit

pensions to offering new hires either 401(k)-type or gcash balanceh plans that

reduce company liability.

Other firms are moving pension liabilities off their books. Last year,

Verizon Communications transferred $7.5 billion in pension obligations — about a

quarter of its total — to Prudential Insurance, to limit its liabilities and

bolster its financial profile. The move came after General Motors paid

Prudential to assume $25 billion of its pension risks.

The decline in traditional pensions has coincided with the erratic stock

market, rising health-care costs and a steep drop in housing values to undermine retirement security for a growing number of

Americans, according to many analysts.

Eroding retirement security has prompted the Obama administration and other

policymakers to search for ways to bolster it. One idea is to establish

automatic individual retirement accounts for the roughly half of the workforce

not covered by a retirement plan on the job. Others want to bolster tax

incentives for low- and moderate-income people to save for retirement. There are

also calls for creating a new tier of retirement savings to supplement

Social Security.

Congress moved last year to provide relief from the pension damage being

caused by low rates by allowing firms to temporarily use a 25-year interest rate

average when calculating how much money they had to funnel into funds.

gIt phases out over the next five or six years,h said Joshua D. Rauh, a

Stanford University professor who studies pension plans.

But the relief does not change how pension liabilities appear on a firmfs

balance sheet. In addition, firms could find that under the new law, their

pension-related liabilities could quickly rise after 2013 unless interest rates

return to more normal levels. This has dampened the appeal of the change for

many companies.

That has left many firms to conclude that it is best to freeze their pension

plans, cutting off contributions for current workers and making new employees

ineligible for the benefit.

At ILM, which sells commercial insurance to building-supply manufacturers and

retailers, the pension plan had been a source of pride in a benevolent company

culture developed over 117 years.

gPersonally, I think a pension is a tremendous benefit,h said Don W.

Blackwell, ILMfs chief financial officer and treasurer. gThis is a very valuable

benefit to our employees. We did not want to take it away.h

But with the pension plan causing the firm to report a $8 million liability

at the end of last year and with no end in sight for low interest rates, gwe

waved the white flag,h Blackwell said. gIt was a waiting game and we blinked. We

had no idea that interest rates would remain this low.h

Once it froze its pension plan, ILM started to contribute 3 percent of each

workerfs salary to a 401(k) plan. Itfs something, but nowhere near enough to

provide the same level of retirement security that the companyfs pension

did.

Blackwell said an employee with a $40,000 annual salary who received a 3

percent raise each year, set aside 7 percent of his pay for retirement and

received a 3 percent company contribution would wind up with roughly a third

less money in his retirement fund after 25 years than he would have with the

pension plan.

Still, ILM employees are taking the pension fundfs demise in stride. gTo be

honest, I am surprised that the plan was not frozen a while back,h said Traci

Barber, 42, a service center manager who has been with ILM nearly 13 years. gI

was surprised when I took this job that it even offered a pension plan.h

Knotts, the firmfs vice president for human resources, said that many

employees do not seem to understand the security that a pensionfs guaranteed

monthly payments offer in retirement. gWhen people get hired here,h she said,

gthey are not thinking about that. All of the questions are about salary and

paid time off.h

She was among the executives who fretted over cutting the pension plan,

deciding to back the decision even though she knew it is bad for employees.

Keeping it, she said, would be even worse for the company.

Surprisingly, she added, the company seemed to value the plan more than some

employees. Only one employee complained, she said. Moreover, when employees

leave ILM, she said, they most often choose to take their pension as a lump-sum

payment rather than as a monthly payment for life. gI guess itfs the lottery

effect,h she said.

ILM retirees who chose to receive the pension on a monthly basis call it the

best decision they could have made. gThis was the first job that offered me the

comfort of a pension,h said Beverly C. Shoemaker, a former secretary who left

the company in 2004 after working there 15 years. gI feel blessed to have it. I

really do feel for the current employees, because I know how much it means to

me.h

David J. Riese, who retired as vice president of claims in 1997 after 16

years at ILM, said he values the security provided by his company pension.

Current employees, he added, will not have it as good.

gThey have to rely on the profitability of a 401(k) and their ability to

manage it,h he said. gTo me that is iffy, at best.h

© The Washington Post Company